Learning as Thinking, Feeling, and Doing

As educators, we know that school has to change but we’re lost in a fog of reform. We’re told that learning should be project-based, place-based, social and emotional, mindful, diverse and equitable. . . with so many directions, it’s hard to see a way forward.

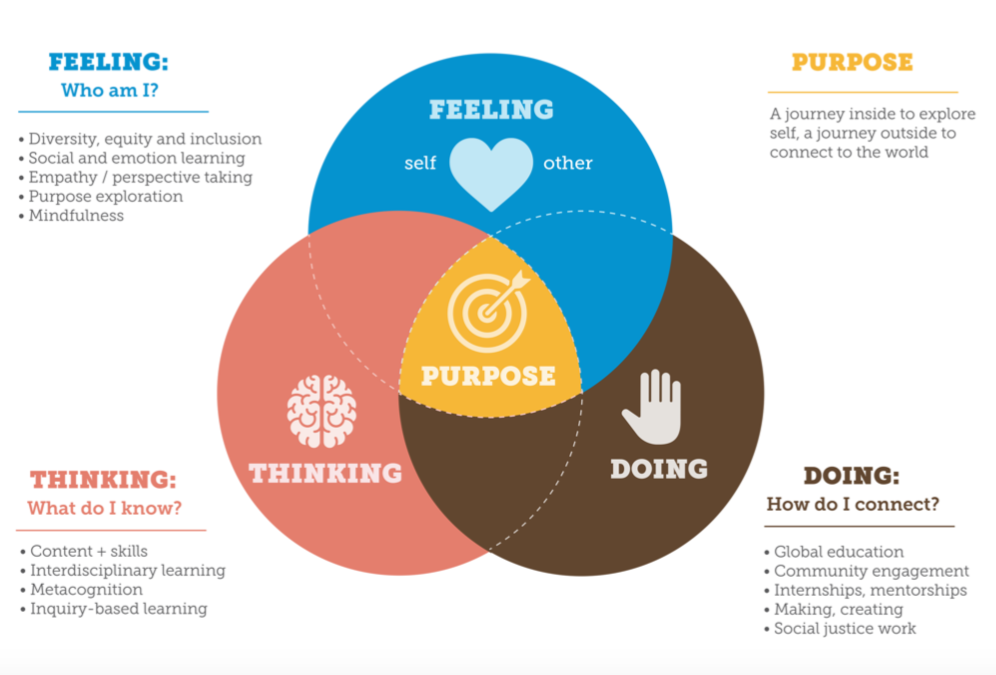

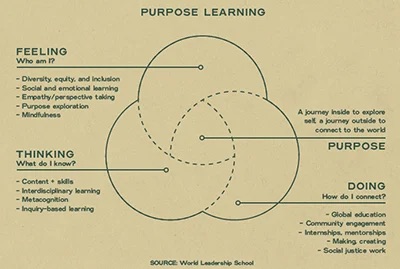

Purpose Learning is a growing movement that integrates today’s school reform into a simple, actionable framework. Learning in the past emphasized thinking, or helping students memorize content and develop key cognitive skills. Learning in the future will integrate thinking with rich forms of feeling and doing, all at the same time. At the center of these three domains students have a chance to explore purpose.

What is purpose?

Stanford’s Center on Adolescence defines purpose as “a stable intention that is meaningful to self and consequential for the world.” In other words, it’s a core of meaning on the inside that connects to an action on the outside. It can be very simple, such as “to grow and give.”

According to medical studies, purpose-driven students are happier, healthier, and sleep better. They are also deeper learners and better stress managers. But only 20% of today’s high schoolers are purposeful, according to Stanford’s Youth Purpose Study.

At World Leadership School, we know we can do better. We help schools pursue deliberate strategies in response to the question we believe is guiding the future of learning: “How can schools help students explore, discover, and articulate purpose?”

Over the last decade, schools have made a broad shift away from content memorization to skills mastery. But even competency-based learning can feel meaningless unless it is designed around the humanity of each student. Purpose learning allows students to explore two basic human questions: “Who am I?” and “How do I connect to the world?”

Purpose learning has profound implications for the future of K-12 learning, including how we assess students, organize the school day, divide knowledge into subjects, and define what it means to be a teacher — and a student. It will require a total reboot of school as we know it and it’s already taking form every day in hundreds of schools around the world.

We believe that having a sense of purpose is not a skill alongside grit, growth mindset, or self control. It is the capstone skill from which these other skills ensue. In an age of artificial intelligence, where everything that can be automated will be automated, our uniquely human ability to tell stories, make meaning, and follow purpose will be more important than ever.

Purpose Learning allows each student to navigate college and life with more direction and clarity. As the world accelerates and becomes increasingly connected, purpose helps students manage volatility and contribute to the common good. Our world needs next-generation leaders more than ever.

Traditionally, emotions have been unwelcome in schools because of long-held cultural beliefs that emotion interferes with thinking. Thanks to recent neuroscience, we know the opposite is true: deep learning happens when we connect thinking to emotion. Helen Immordino-Yang, a brain researcher at the University of Southern California, writes:

“It is literally neurobiologically impossible to build memories, engage complex thoughts, or make meaningful decisions without emotions. Put succinctly, we only think deeply about things we care about.”

Yang and other scientists have studied brain scans of students involved in meaningful learning. What they find is that deep learning activates not only the cerebral cortex, our “thinking brain,” but also the primitive, limbic parts of the brain that are related to human survival.

Scientists also recognize the deep mind-body power of learning by doing. By involving our bodies in making, creating, and applying our thinking, students cement their learning. Students experience greater emotion and therefore deeper learning when working on real problems with real people.

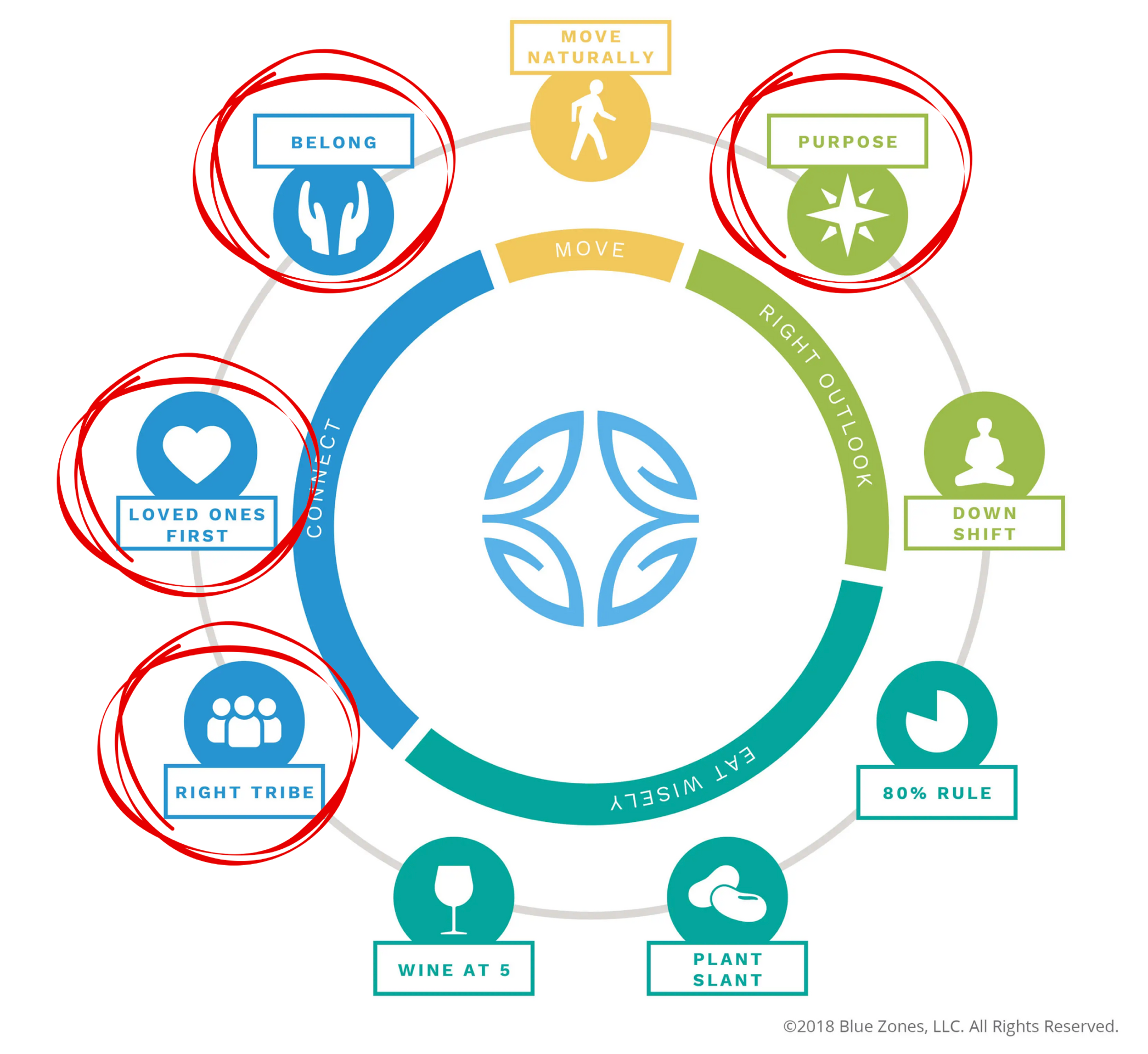

Blue Zones Power Principles

Aristotle explored the differences between what he called hedonic and eudaimonic happiness in the Nichomachean Ethics (350 BCE). He associated hedonic happiness with pleasure and fulfilling drives like hunger, thirst, etc. Aristotle associated eudaimonic happiness, which he said only humans can experience, with living a life of virtue. Hedonic is about taking for oneself, eudaimonic is about giving to a larger collective.

Friedrich Nietzsche was a 19th-century existentialist philosopher who identified the uniquely human ability to make meaning even when religion and other meaning systems break down. “Those who have a ‘why’ to live can bear almost any ‘how’,” wrote Nietzsche in Twilight of the Idols. Viktor Frankl, an Austrian psychiatrist and survivor of the Holocaust, takes Nietzsche’s idea further. He found that fellow prisoners who were able to find meaning in their suffering and connect to a purpose outside of themselves often had a higher chance of survival. In his world-famous Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl wrote:

“. . . everything can be taken from many but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in a given set of circumstances, to choose one’s way.”

The long-running philosophical discourse around life purpose continues today in Positive Psychology, a broad movement to understand happiness, meaning, and eudaimonia, or the “good life”. The movement was launched in 1998 by Martin Seligman, who as President of the American Psychiatric Association, extolled his colleagues to move away from focusing solely on mental illness and also explore what makes humans thrive. Since then, thousands of medical and scholarly studies have advanced the study of human thriving. Researchers at Stanford’s Center on Adolescence, most notably Dr. William Damon, have studied how schools can help students develop purpose.

The idea of “head, heart, and hands” learning was advanced by Swiss pedagogue Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi in the early 19th century. This concept was incorporated into school models by progressive educators such as Rudolf Steiner, Maria Montessori, and John Dewey. Progressive education, a vital reform movement in the USA in the early 20th century, was completely overshadowed by the “factory school model” that scaled quickly after WWII in response to a growing population. That model allowed high school graduation rates in the US to go from 6% in 1910 to almost 80% in 1970, where it has remained nearly flat ever since. With alarming rates of anxiety and depression among youth, a new approach to education is needed. At World Leadership School, we have used recent neuroscience to reinvent “head, heart, and hands” learning as Purpose Learning, or learning as thinking, feeling, and doing.

Here are common myths of purpose, according to best-selling purpose author Richard Leider.

- Purpose is a

luxury→ Medical studies prove that purpose is fundamental to happiness, health, and learning. - Purpose is a

cause→ Purpose can be simple and does not have to save the world, though it does have to contribute to something beyond self. For instance, a child who enjoys doing stand-up comedy might identify with “lighting up the room so others smile.” A child who has a sibling with a learning disability might want to help “others overcome barriers to thrive.” - Purpose is a

single passion→ Research has shown that telling students to “follow their passion” can actually close doors and limit growth. Purpose is a stable, abstract intention that comes alive through the many passions and phases of a person’s life. - Purpose is

revealed→ Purpose is rarely revealed in a “mountain top” moment. Most often it is revealed through daily, disciplined practice. Staying on a path of purpose requires sacrifice, and focused time for exercise, rest, reflection, goal setting, and connecting with like-minded people in community.

Beyond Thinking: What If the Purpose of School Were Purpose?

Ross Wehner and Jessica Catoggio, National Association of Independent Schools, Fall 2023

Purpose is a unique journey for each human, and it’s an expedition that varies dramatically for each school. In our experience, each school enters the purpose-learning framework from different places. Many independent schools enter via learning as thinking, while others focus on doing via project-based, arts-focused, or expeditionary learning. Where independent schools can often grow is learning as feeling — in other words, the part of purpose learning where students drop into emotion, see others with empathy, and have the space and support to do the inner work of identity and purpose clarification.

Using Purpose Learning to Increase Belonging in the Classroom

Jessica Catoggio, The EARCOS Triannual Journal, Fall 2023

As purpose is a two-way journey, Purpose Learning is analogous to a busy, two-way street in which the “drivers” dynamically change lanes, detour at will, trail in the fast lane or slow depending on the road conditions, navigate roundabouts, and thoughtfully make return trips. Traveling one way on this busy street, “drivers” internalize and connect learning to self. In the other direction, the journey allows students to connect learning to the world outside of self in ways that are rich and meaningful.

On Purpose: Reimagining What and How Students Learn

Ross Wehner, Independent School Magazine, Winter 2022

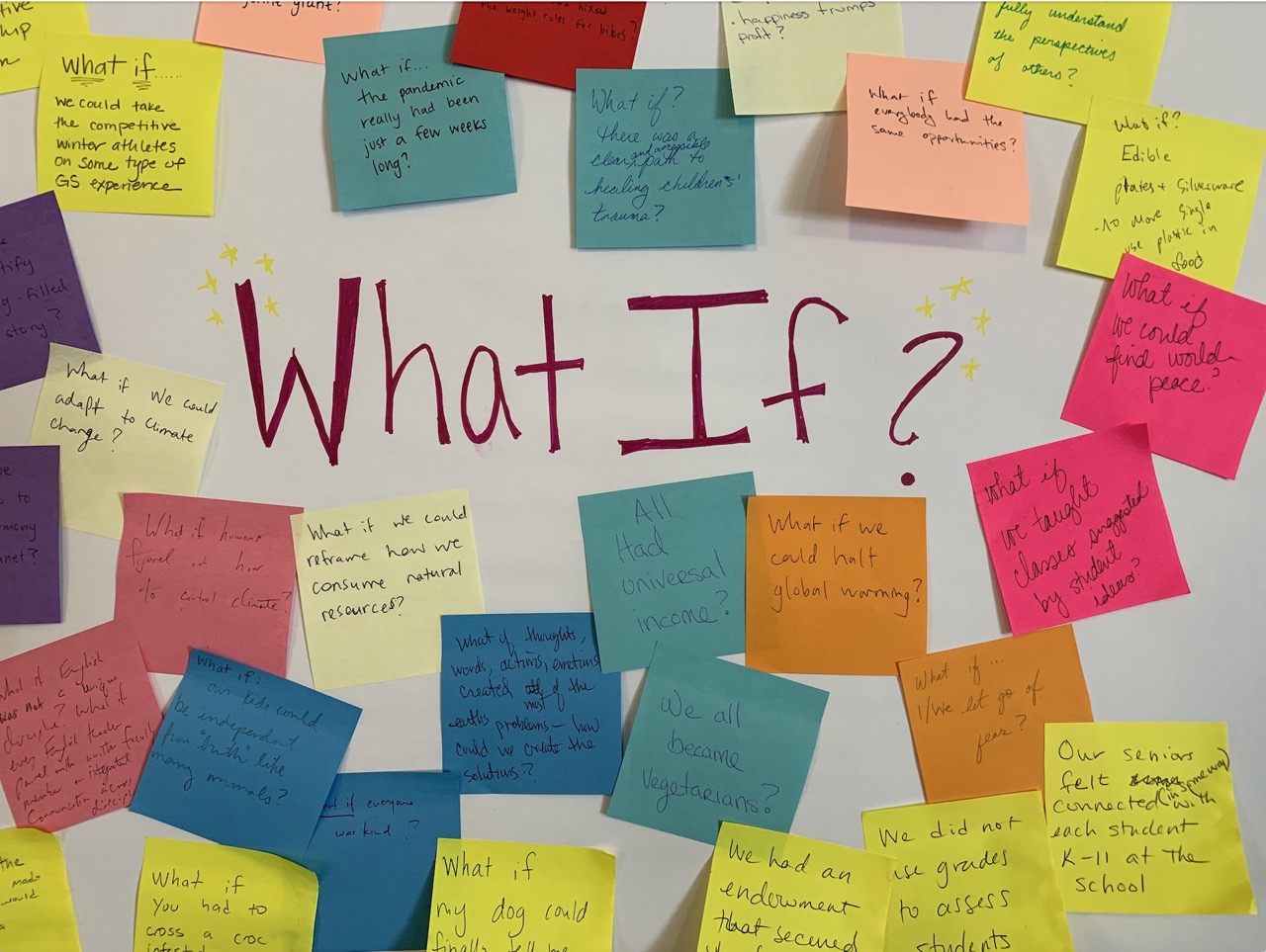

Schools are already doing such great work around purpose formation. But we need to be more explicit by understanding the theory and science behind purpose formation. We need to tie together what we are already doing into a visible K–12 strategy designed to foster purpose among students. We need to formulate the right questions: Now that we understand how the adolescent brain works, how can we make it light up with purpose? Or more specifically: How can K–12 schools help students discover, explore, and articulate purpose? What if the purpose of school were purpose?

Explore WLS

Student travel locations

Explore WLS

Student travel locations